The 1824 presidential election differed from former contests in two important ways. During the “Era of Good Feelings,” the nation had largely become a one-party system under the Democratic-Republicans, meaning there was no division between candidates of opposing political parties. There was also no clear political successor to President James Monroe.

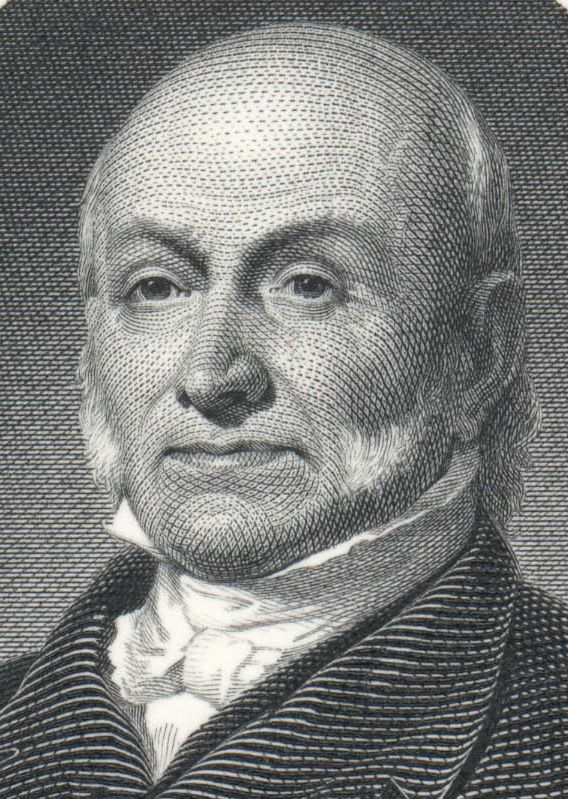

This leadership void created an unprecedented contest among several potential candidates, three of whom served in Monroe’s cabinet: John Quincy Adams, secretary of state; John C. Calhoun, secretary of war; and William H. Crawford, secretary of the treasury. Henry Clay, Speaker of the House of Representatives, and the war hero General Andrew Jackson rounded out the list of competitors.

In 1824 “electioneering”—campaigning today—was undertaken by political operatives and not the candidates themselves. Campaign literature largely sought to promote one candidate while avoiding serious personal attacks on the opposition.

When the votes were tallied, Jackson received the most popular and the most electoral votes; however, he did not obtain the requisite majority of electoral votes. Per the process laid out in the US Constitution, the decision fell to the House of Representatives, where each state had one vote between the top three candidates—Jackson, Adams, and Crawford. On 9 February 1825, the House elected Adams on the first ballot.

After the election Jackson and his supporters claimed there had been a "corrupt bargain" between Adams and Henry Clay, who became Adams’s nominee for secretary of state. Clay maneuvered to push the House vote to Adams, but this likely reflected Clay's doubts about Jackson's qualifications for the office rather than an arrangement with Adams.

On 4 March 1825, John Quincy Adams was inaugurated as the sixth president of the United States. He and his family were not prepared for the toll the office would take on them. Almost immediately, the race for the 1828 presidential election began. Jackson and his supporters, believing that the 1824 election had been stolen, sought to ensure he was successful four years later. Against this challenging backdrop, Adams pursued an ambitious but largely unsuccessful executive agenda, including federal funding for internal improvements and improved commercial relations with Latin American nations.

The rematch between Adams and Jackson in the 1828 election was one of the most bitterly fought and rancorous in US history. The two candidates were routinely lauded by their supporters and maligned by the opposing press. In a new era of political mudslinging, even the candidates’ wives—Louisa Catherine Adams and Rachel Jackson—became targets for the smear tactics.

This time Jackson emerged with a clear majority over Adams in both the electoral and popular votes. A disappointed, one-term president, Adams nonetheless stepped aside, ensuring a peaceful transfer of power.

Explore a selection of Election-related materials:

John Quincy A dams, Diary, 15 May 1824: Adams and Jackson had a largely positive relationship prior to the 1824 election. Adams believed, “There was no person who could be substituted for Jackson to fill the Vice-Presidency,” and Jackson found Adams to be “a man of the first rate mind of any in america" (Jackson to James Gadsden, 6 December 1821, Library of Congress).

dams, Diary, 15 May 1824: Adams and Jackson had a largely positive relationship prior to the 1824 election. Adams believed, “There was no person who could be substituted for Jackson to fill the Vice-Presidency,” and Jackson found Adams to be “a man of the first rate mind of any in america" (Jackson to James Gadsden, 6 December 1821, Library of Congress).

John Quincy Adams, Diary, August 1824: Adams regularly decried the 1824 electioneering in his diary. “It seems as if every liar and calumniator in the Country was at work day and night to destroy my character.”

Unknown to John Quincy Adams, 27 January 1825: This anonymous letter from "A Sincere Friend" warned Adams that his “name . . . will be cursed if you consent to stand in opposition to Andrew Jackson in the House.”

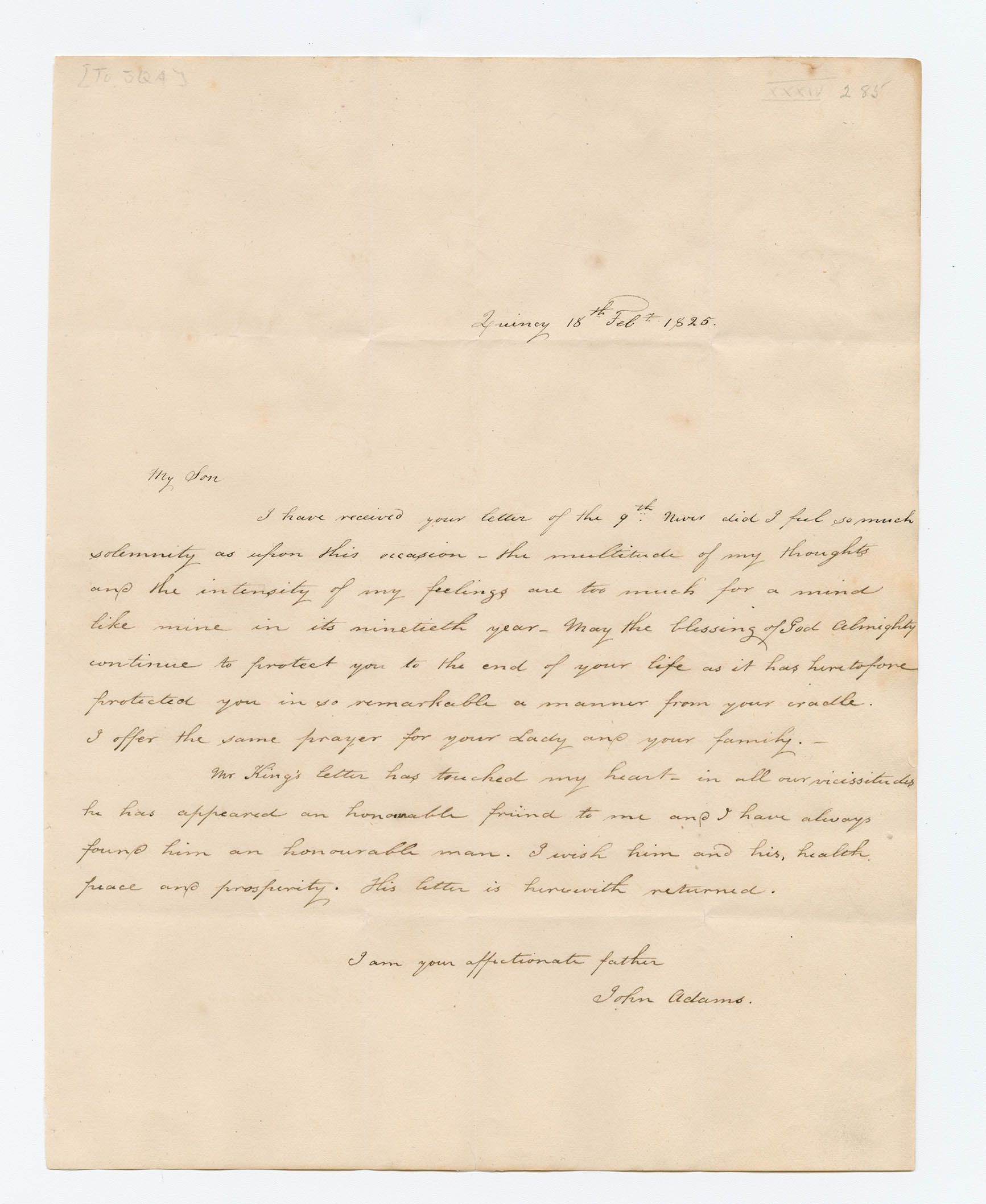

John Adams to John Quincy Adams, 18 February 1825: “Never did I feel so much solemnity as upon this occasion,” father wrote to son, offering his blessings after learning the outcome of the 1824 election.

John Quincy Adams, Diary, 17 December 1827: Well before the 1828 election, Adams saw the writing on the wall. “When suspicion has been kindled into popular delusion, truth, and reason, and justice spoke as to the ears of an Adder—the sacrifice must be consummated, before they can be heard— General Jackson will therefore be elected.”

Charles Francis Adams, Diary, 31 October 1828: “This is the day upon which the great Presidential question which has so long agitated the Country commences to assume a definitive result. And our family are at last to cease being the eternal subjects of contention and abuse.”

Printed Propaganda

Sketch of the Life of John Quincy Adams

1824. Adams was one of the first presidential candidates to employ the device of a campaign biography (written by him and his father, John Adams).

Adams Ode For the Fourth of March

Written by Charles Sprague, 1825. This is one of several odes celebrating Adams's election.

"Adams by fraud ascends, Freedom's in tears"

In June 1825 Adams received an anonymous newspaper clipping condemning the "corrupt bargain."

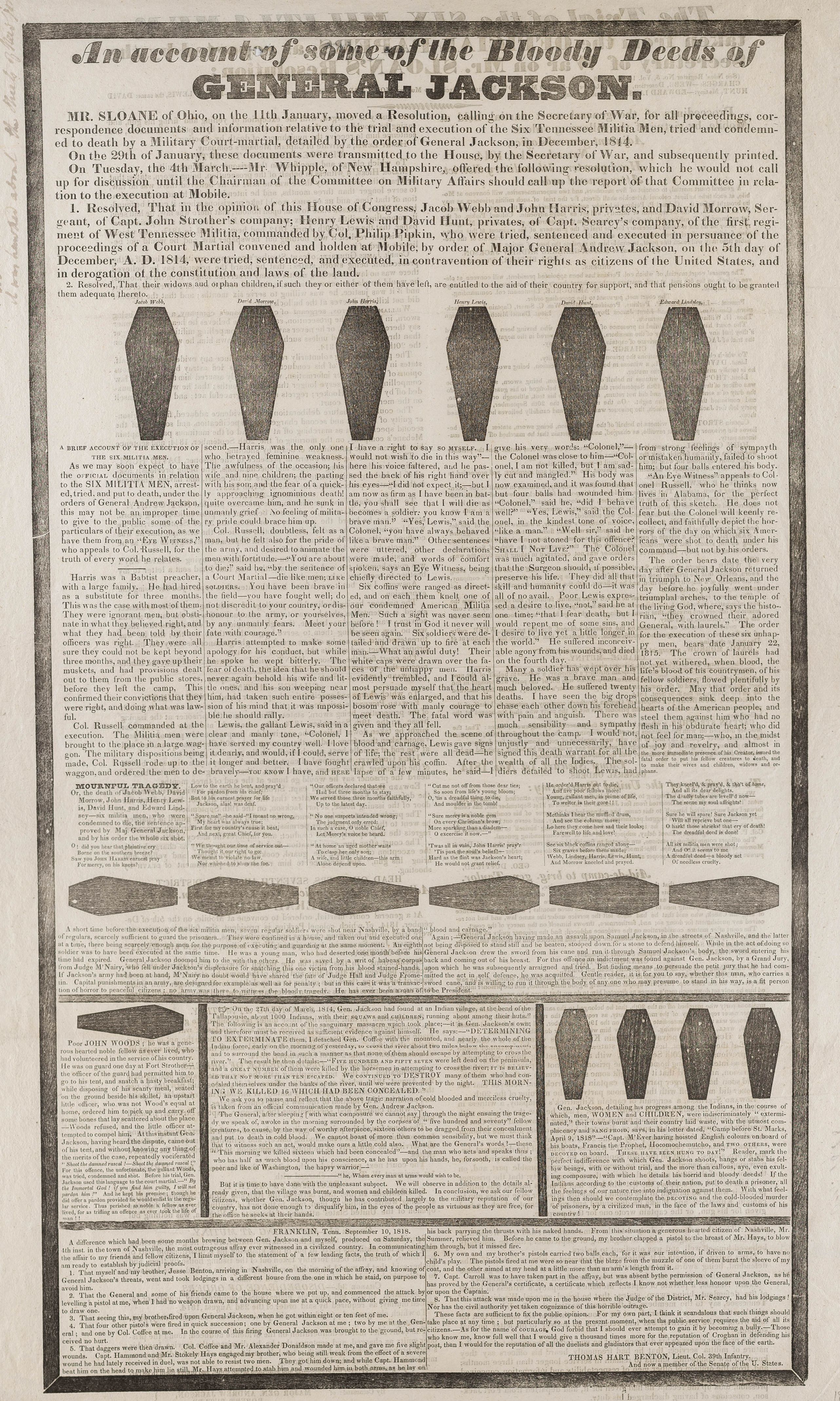

"An account of some of the bloody deeds of General Jackson"

Also known as the Coffin handbill, 1828, this anti-Jackson political propaganda details the execution of six militia men under Jackson’s orders.

Campaign Songs

Listen to a campaign song written in support of John Quincy Adams in 1828.

See also this recording of a pro-Jackson campaign song.

Additional Resources

Readers seeking additional primary source materials may wish to explore the John Quincy Adams Digital Diary and The Papers of Andrew Jackson.

Students and educators can visit the primary source set “The bitterness and violence of Presidential electioneering”: John Quincy Adams on the campaign trail, 1824-1828, part of the MHS History Source.

Visit the Adams Bibliography for further readings on John Quincy Adams. The following is a select list of publications related to the 1824 and 1828 candidates and elections:

- Mark R. Cheathem, Andrew Jackson, Southerner, LSU Press, 2013.

- Mark R. Cheathem, The Coming of Democracy: Presidential Campaigning in the Age of Jackson, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018.

- David S. and Jeanne T. Heidler, Henry Clay: The Essential American, Random House, 2010.

- Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848, Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Albert D. Kirwan, "Congress Elects a President: Henry Clay and the Campaign of 1824," The Kentucky Review, Vol. 4: No. 2, Article 2 (1983).