By Nancy Heywood, Lead Archivist for Digital and Web Initiatives

MHS recently launched the MHS Digital Archive, a system that preserves and provides access to born-digital files and reformatted audiovisual material. Our last blog post provides an overview of the Digital Archive and how to search its contents. This post shares some specific examples for adventurous readers to explore!

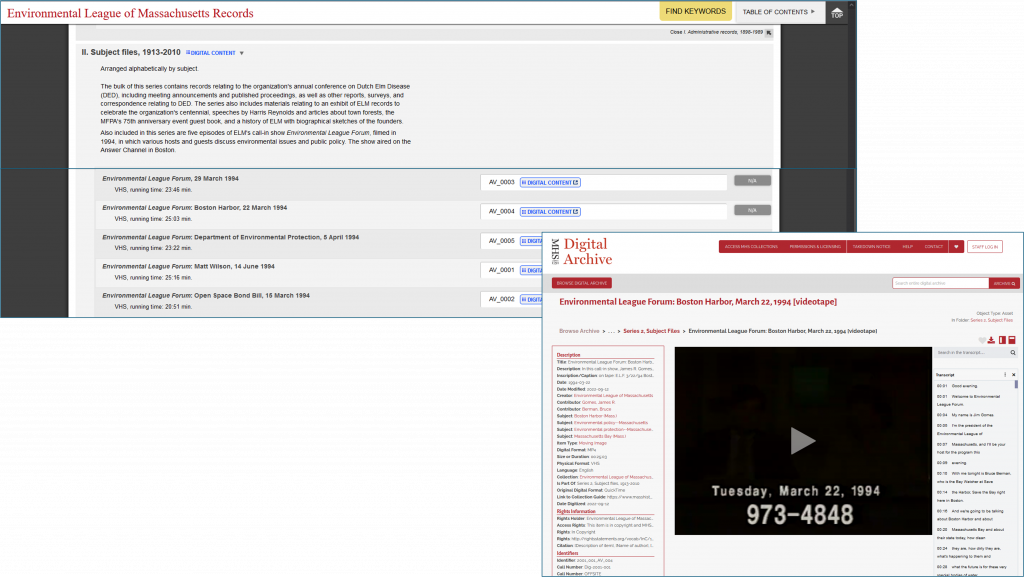

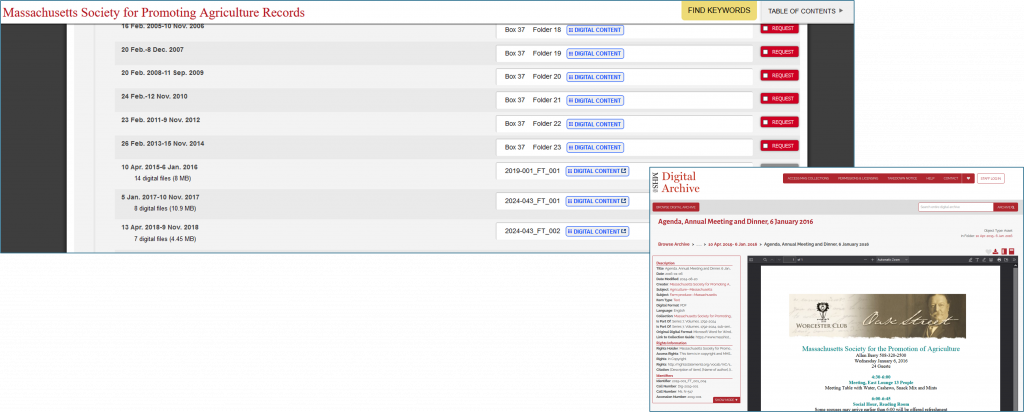

MHS’s digital preservation system is a multi-faceted tool that allows us to responsibly ingest (accept), describe, manage, migrate, monitor, and make digital files accessible. The availability of reformatted audiovisual files via the MHS Digital Archive is especially significant because we don’t have any other way to make audio tapes; cassettes; and VHS, beta, and 16mm films accessible to researchers.

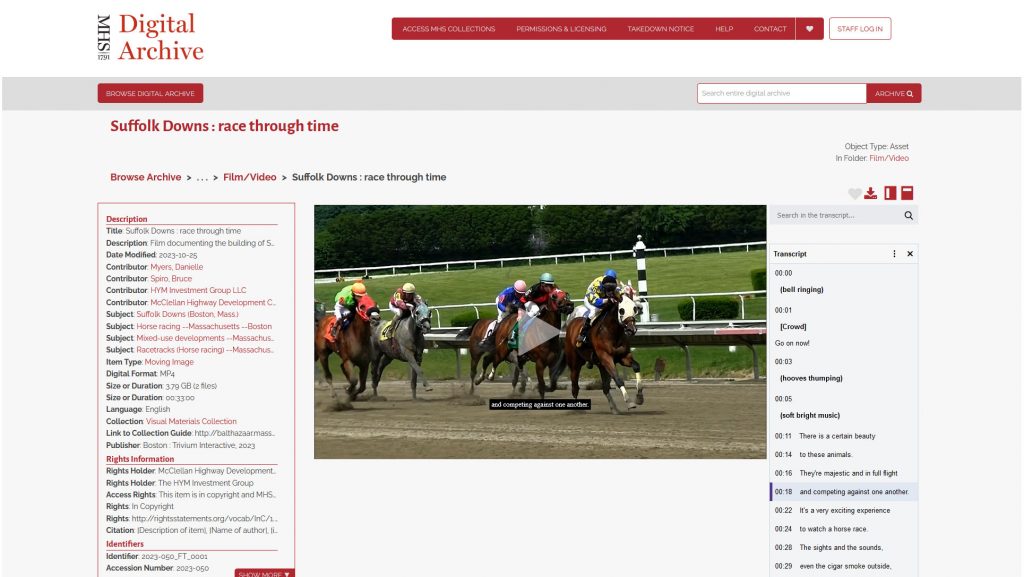

Video about the history of Suffolk Downs

Item: This stand-alone digital video created in 2023, Suffolk Downs: Race Through Time, focuses on the history of the East Boston racetrack and legalized betting and horseracing in Massachusetts.

Example of a digital video: When MHS accepted this digital video, we knew we would be storing the file and the metadata in our digital preservation system and making it available via the MHS Digital Archive.

Explore in the MHS Digital Archive or start with the catalog record in ABIGAIL and follow the link.

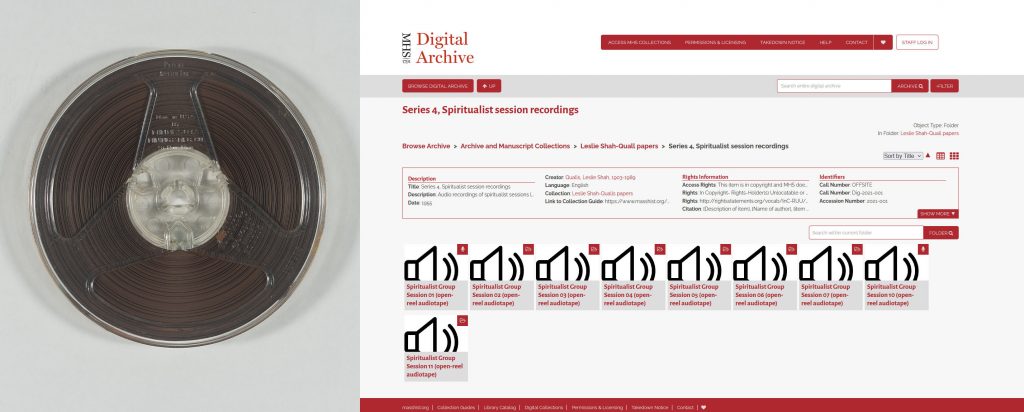

Spiritualist session recordings from the Leslie Shah Qualls papers

Collection: Leslie Shah Qualls (1903-1989) was a spiritualist who conducted psychic readings and mediumship. Her papers mainly consist of her spiritual writings but also contain audio recordings of spiritualist sessions she led.

Example of reformatted audio tapes: The original open reel audio tapes (nine audio tapes, seven with content on both sides) were converted to 16 digital files to provide access to the content. These tapes were in poor condition and required reformatting to preserve the information on them. Even if the tapes were in better condition, archival repositories don’t generally make original AV materials available in reading rooms because of the significant logistics of providing playback equipment for old formats to researchers, as well as the risk of damage or deterioration to the originals during repeated playbacks.

Explore in the MHS Digital Archive or examine the guide to the full collection and follow a link to a specific audio file.

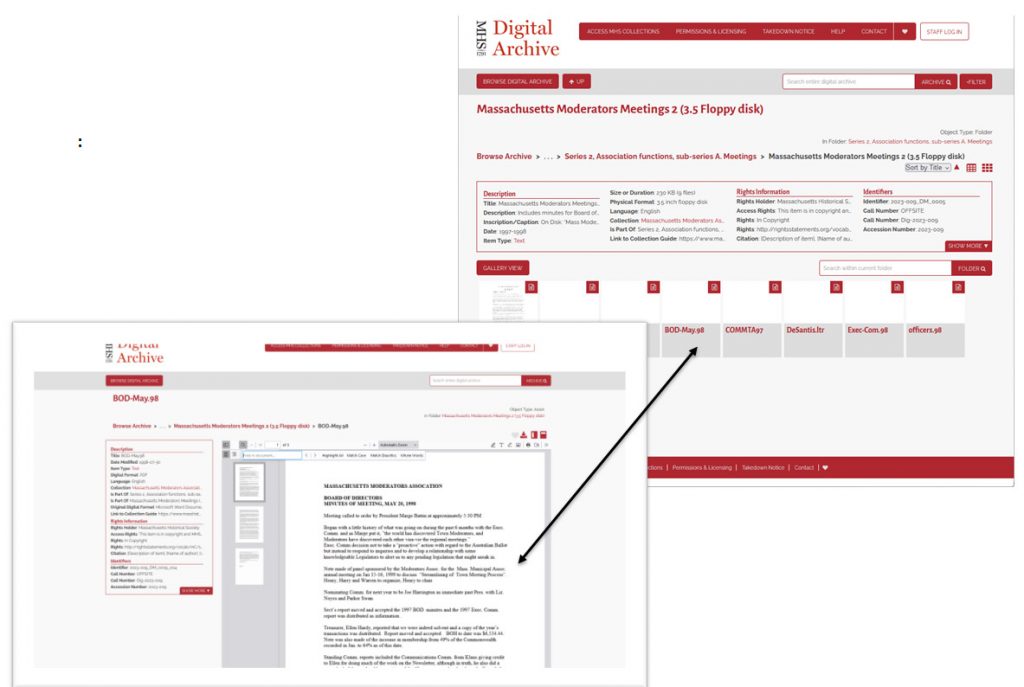

Massachusetts Moderators Association records

Collection: The Massachusetts Moderators Association was founded in 1957 and provides resources and collaboration opportunities to town moderators. The collection was donated in 2023 and is comprised of both physical and digital files.

Example of born-digital files: The digital materials within the Massachusetts Moderators Association were created as electronic documents in formats such as PDF and open-doc spreadsheets. These files include meeting minutes, lists, and digital files relating to various handbooks to help those leading town meeting sessions.

Explore in the MHS Digital Archive or read the guide to the full collection and follow the links to the digital files.