by Hilde Perrin, Library Assistant

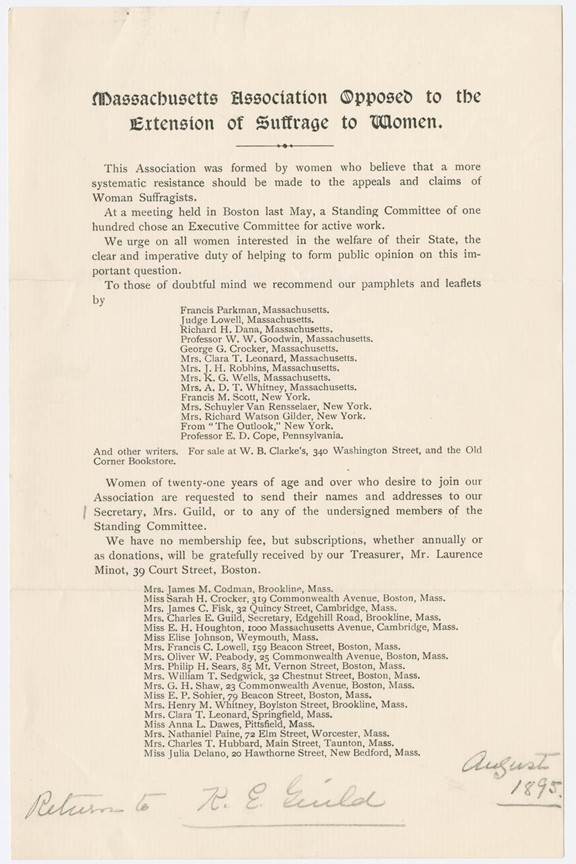

While March’s Women’s History Month has just concluded, women’s history is still present in our collections here at the MHS. Our collections are full of inspiring women, many of whom advanced and advocated for women’s rights through their lives and work. But the complexity of history also means that many women worked against women’s rights, and their material has also been preserved. Through working on a project to create a subject guide of women’s suffrage materials held by the MHS, I discovered that we own a large collection of anti-suffrage material from the debate around women’s right to vote and the passage of the 19th amendment. Among this material are the records of the Massachusetts Association Opposed to the Further Extension of Suffrage to Women. Established in 1895, this association worked to combat the rise of feminist suffragists and argued that the vote should not be extended to women. While it is often assumed that women’s suffrage was hampered by men, these records show that there were also women who felt strongly opposed to suffrage and organized against it.

Donated to the MHS by the estate of Mrs. Randolph Frothingham in 1946, the records contain several copies of bylaws and overviews of the work of the association, which detail the belief held by these women, and the pattern of work they took part in to share their views. Women over the age of 21 who were “interested in the welfare of their state” were encouraged to become members, with no membership fee limiting their participation. The association advanced its cause through three branches of work: legislative, educational, and constructive. The legislative work included contacting and informing members of the legislature about their opposition to women’s political rights. The educational branch promoted print material, including pamphlets and magazines, and organized public audiences to increase the general knowledge of their cause. The constructive work focused on building the membership of the association, mainly working through members and local community organizations to build relationships and encourage the spread of anti-suffrage ideals.

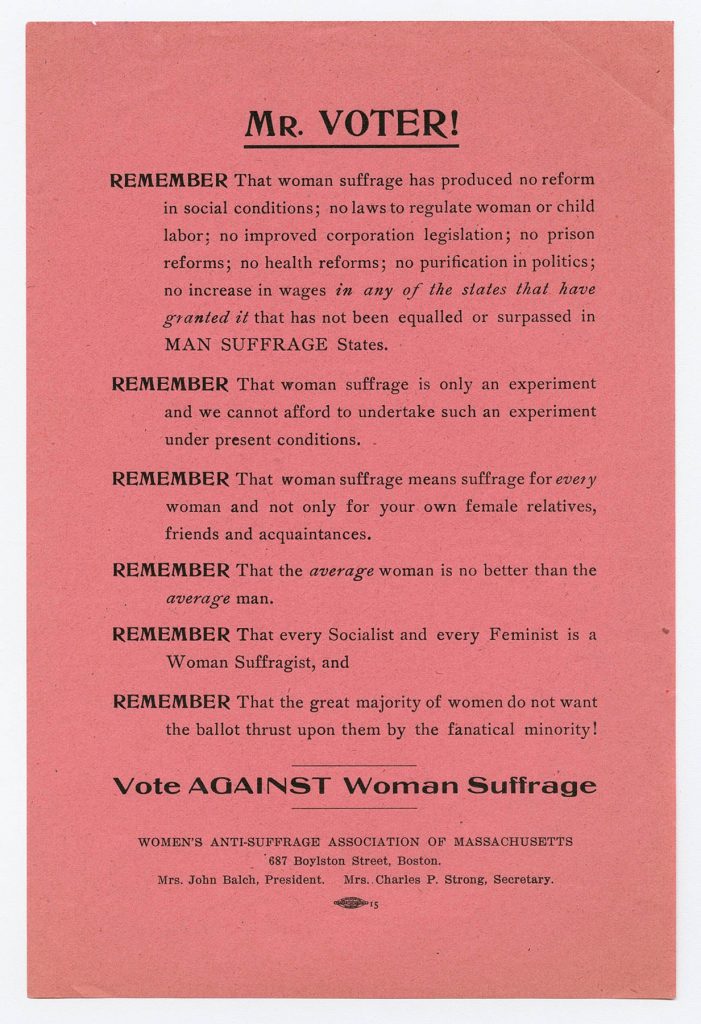

An example of the educational material circulated by the anti-suffrage association includes a pamphlet addressed to “Mr. Voter.” Printed on red paper, it reminds male voters that women’s suffrage is “an experiment,” and that “the great majority of women do not want the ballot thrust upon them” by what the pamphlet calls a “fanatical minority.” Reminding readers that the “average woman is no better than the average man,” the pamphlet urges the reader to “Vote AGAINST woman suffrage.” The pamphlet typifies the association’s anti-suffragist sentiment, reminding us of the complexity that exists within our collections and history at large.

For more information about the women’s suffrage movement in Massachusetts, visit the digital feature “Massachusetts Debates a Woman’s Right to Vote,” and be on the lookout for a new subject guide coming out in the next few months about our women’s suffrage materials!