by Gwen Fries and Rhonda Barlow, The Adams Papers

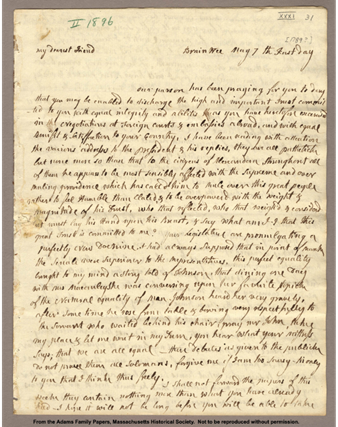

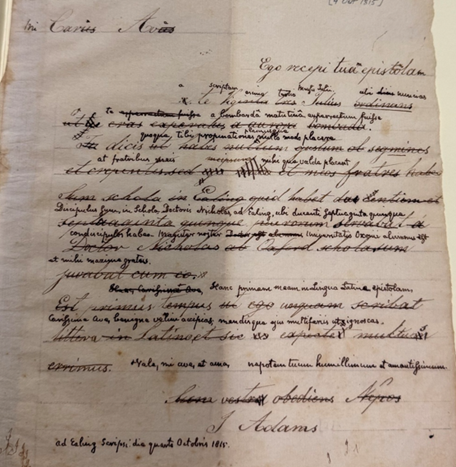

On 4 October 1815, twelve-year-old John Adams II sat down at a desk outside London to write a letter to his grandfather. The middle child of John Quincy and Louisa Catherine Adams had spent several years of his life being raised by John and Abigail on their farm, Peacefield, while his father and mother served in a diplomatic role in St. Petersburg, Russia. Now reunited with his parents, John II wanted to write a letter to his grandfather to show how far his education had come. His little brother, Charles Francis Adams, had just composed a letter in French. Not to be bested, John II was going to do it in Latin.

The problem was John II was an indifferent scholar. He loved to be the center of attention, stalking his aunts and cousins around Peacefield and chattering incessantly. What he possessed in charm and charisma, he lacked in concentration. Thus, his father insisted on looking over the letter before it was sent. John Quincy, ever the perfectionist, had some thoughts.

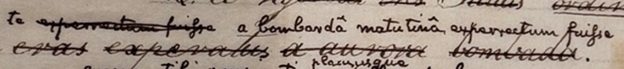

Rarer than an extant copy of a child’s Latin is an extant draft of a Latin composition. We’re given a clear visual of how he thought through each word of the letter and how his father refined it. I could see the juvenile writing and the interlineated corrections, but I had to tag in Adams Papers research associate Rhonda Barlow to make sense of what I was seeing. She translated John II’s letter thus:

My dear grandfather,

I received your letter from you on 23 July beginning that you were awakened by a morning bombardment. You say that you have no taste for noisy rattling and clapping, but I have and my brothers have.

I am a student at Ealing which has 275 boys served by Dr. Nicholas from the schools of Oxford[.] I am very pleased with him.

It is the first time that I ever wrote a letter in Latin, and thus you will expect I make many mistakes.

I am your obedient grandson

J Adams

Then she translated John Quincy’s interlineations:

My Dear Grandfather

I received your letter written by you on the 23d of the month of July where you reported that you were awakened by a morning bombardment.

You say that you take no pleasure in applause and toasts but they are pleasing to my brothers and I.

I am a student in the school of Dr. Nicholas, at Ealing, where I have 275 fellow-students. Our teacher, the doctor, is an alumnus of Oxford University, and I am very grateful.

This letter is my first in the Latin language, Dearest Grandfather, I wish you to receive it kindly; and that you forgive its many faults.

Farewell, my grandfather, and love, your most humble and most loving grandson.

J. Adams

Barlow explained to me that JQA’s edits were in the spirit of conforming more to classical Latin. The one exception to this is the word “bombarda,” which John II likely plucked out of the Ainsworth Latin Dictionary, and which his father and grandfather enjoyed. (To be fair to the tweenager, classical Latin wouldn’t have a word to mean gun, and it’s the noisy nature of guns that’s key to the sentence.)

The letter went from the composition of a careless child to the product of a skilled linguist. “Your classical letter of the 4th. of Octr, does you honour, upon every Supposition that I can make,” his delighted grandfather responded on 14 Dec. 1815. However, a hint of suspicion crept in amongst the praise. “If you have composed it yourself, it is highly honourable to the Skill and care of your Preceptors and to your own Application to your Studies; All of which must have concurred in producing Such a proficiency in so Short a time.”

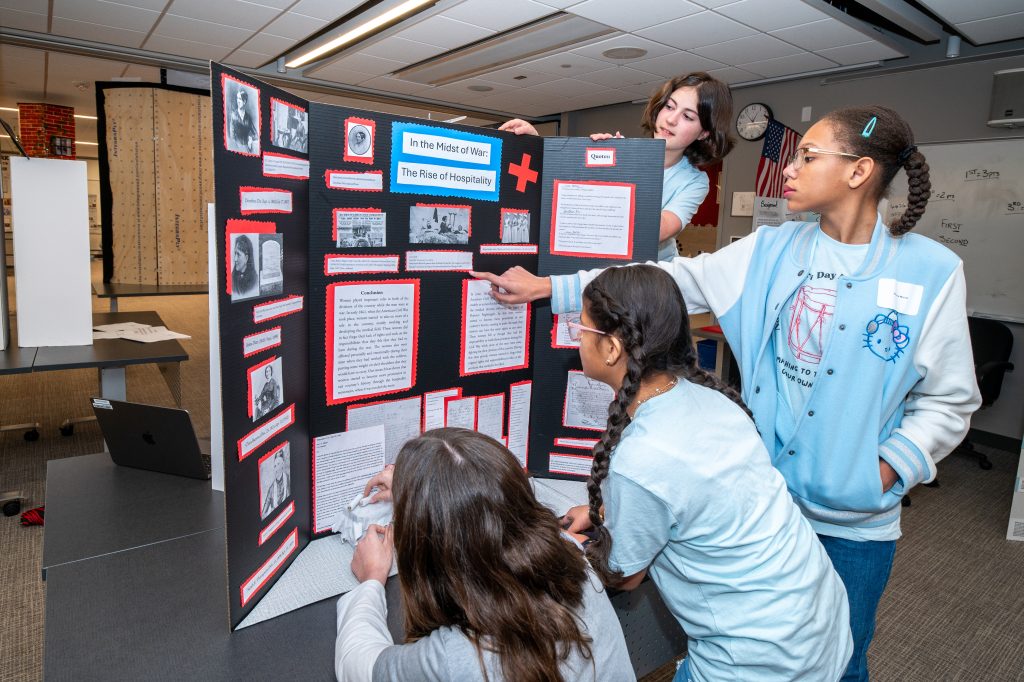

The Adams Papers editorial project at the Massachusetts Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the generous support of our sponsors. Major funding of the edition has been provided by the Packard Humanities Institute, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the National Historical Publications and Records Commission.