by Susan Martin, Senior Processing Archivist

When Ellis Dexter Atwood died in 1950, 1,500 people attended his funeral. What made him so beloved? One reason was the Edaville Railroad in South Carver, Massachusetts.

The story of Edaville began in 1941 when Atwood, one of the country’s leading cranberry growers, purchased historic railroad cars, tracks, and equipment from a defunct Maine railway. Atwood knew these narrow-gauge cars would be ideal for working his cranberry bogs. By 1947, he had transferred this equipment to his 1,800-acre estate in South Carver and built 5.5 miles of track for transporting supplies in and cranberries out. He also offered free rides to friends, and these rides soon became a popular weekend tourist attraction. Just three years later over 2,000 people a day were visiting Edaville.

Railroad enthusiasts were, even then, fascinated by these vintage narrow-gauge railroads, which at two feet wide were less than half the standard. Three months after Edaville opened, one such enthusiast named Martin Schmidt wrote Atwood for more information, and Atwood sent him some mimeographed promotional literature on the history of narrow-gauge railroads and Edaville in particular. Those papers are here at the MHS.

This unassuming collection turned out to be a lot of fun to research. I found some terrific contemporary write-ups on Edaville in Popular Mechanics (1949) and The Baltimore & Ohio Magazine (1950).

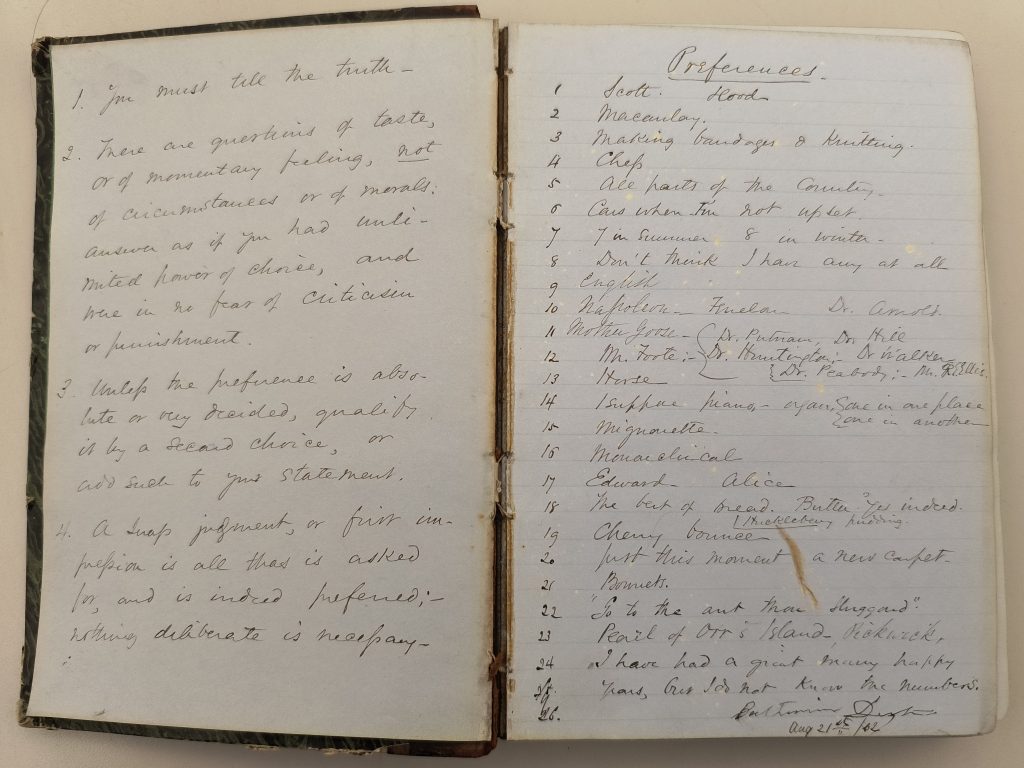

Railfans will find a lot of detail in this small collection to interest them, but my main takeaway is that Atwood was funny! I love to find humor in historical manuscripts, which can sometimes feel dry and inaccessible. The collection includes a hilarious proto FAQ written by Atwood. Among the usual questions about hours and directions, we also find these:

How can a young fellow start a cranberry bog of his own if he has no money?

Ans[wer]. Get on the good side of your rich aunt or better still, marry a wealthy girl. If you can’t do either, forget about the whole thing for the present.

Why did you name it Edaville?

Ans. Well, E.D.A. are my initials and we had to call it something.

Why don’t you run your trains according to the time table?

Ans. Well, we try to, but what do you care? The road doesn’t go anywhere and besides, the time table is a souvenir.

Why don’t you run your trains later in the day?

Ans. Well, I suppose our employees are more or less human and they get tired at the end of the day.

Why did you by [sic] this junk?

Ans. I haven’t had time to figure out a reason yet.

Sadly, Ellis D. Atwood died at the age of 61 from a boiler explosion at the Edaville screen house. While he and his wife Elthea left no children, they clearly left a lot of happy memories, and visitors reported that Edaville drivers always blew their train whistles twice when passing near the spot where he’s buried.