by Hannah Elder, Associate Reference Librarian for Rights & Reproductions

Today, we return to the transcription of Clara E. Currier’s 1925 diary. Currier was a working-class woman who lived in or near Haverhill, MA. Her diary records her daily activities—from fiber arts to paid employment to observations of the natural world—and provides insight into daily life a century ago. You can find entries for January and February in past blog posts.

March sees Clara further engaged with civic life, with a town meeting, a vote, and multiple class meetings. She makes a number of social calls, both at homes and at hospitals, and goes to the movies twice. March 1925 is filled with many “fair” days. May March 2025 fare the same!

Mar. 1, Sun. Rain and snow with wind in afternoon went up to see Aunt Frannie and Mae Tenney

Mar. 2, Mon. Fair, worked until six, went to town meeting with Mrs. Dennis and Sizzie.

Mar. 3, Tues. Fair, worked until six, went to mock town meeting at the grange.

Mar. 4, Wed. Fair, worked until six.

Mar. 5, Thurs [$] 21.66 Rain, worked until six, went to the pictures with Mrs. Dennis and mother.

Mar. 6, Fri. Fair, worked until six, went up town.

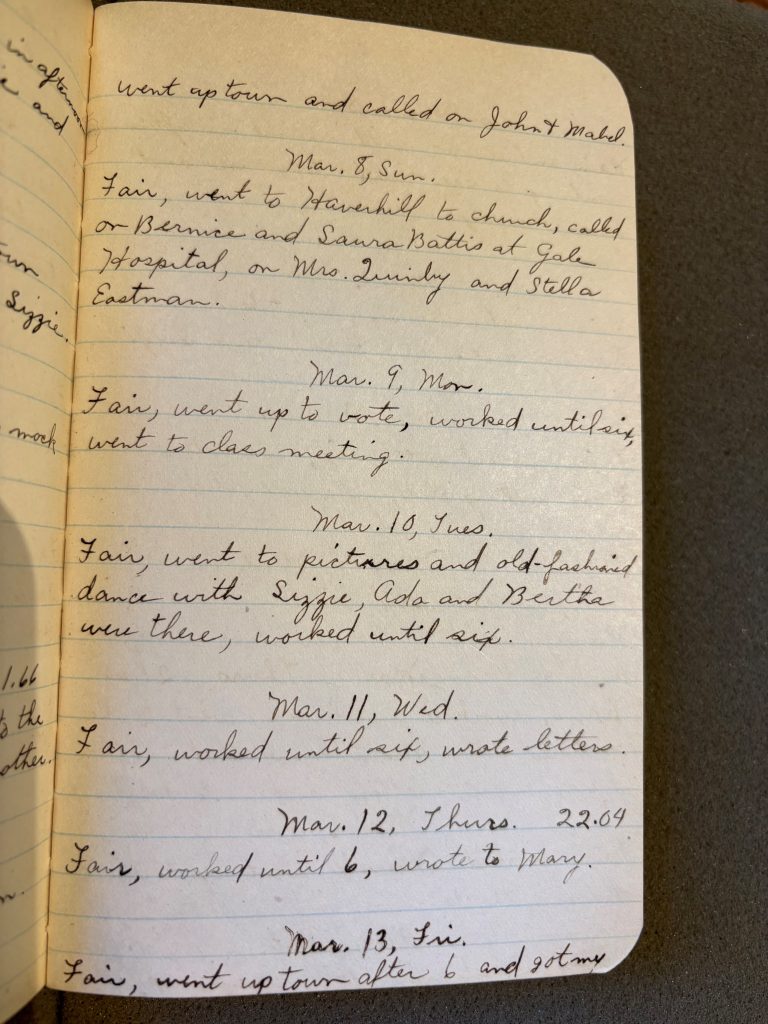

Mar. 7, Sat. Fair, worked until four, cleaned up, went to town and called on John + Mabel.

Mar. 8, Sun. Fair, went to Haverhill to church, called on Bernice and Laura Battis at Gale Hospital, on Mrs. Quimby and Stella Eastman.

Mar. 9, Mon. Fair, went up to vote, worked until six, went to class meeting.

Mar. 10, Tues. Fair, went to pictures and old-fashioned dance with Sizzie, Ada and Bertha were there, worked until six.

Mar. 11, Wed. Fair, worked until six, wrote letters.

Mar. 12, Thurs. [$]22.04 Fair, worked until six, wrote to Mary.

Mar. 13, Fri. Fair, went up town after 6 and got my electric iron (Universal).

Mar. 14, Sat. Rainy, went up town and called on Mrs. Merril. Worked until noon.

Mar. 15, Sun. Fair, went to S.S. and over to see Aunt Abbie.

Mar. 16, Mon. Fair and cooler, Got out at 5 o’clock, cooked, and mended.

Mar. 17, Tues. Rainy, went to Corner class supper and to Grange.

Mar. 18, Wed. Fair, wrote letters and made doughnuts.

Mar. 19, Thurs. [$]20.90 Rain with thunder and lightning. Went over to John’s and they were going to bed.

Mar. 20, Fri. Fair, went to concert at Methodist Church.

Mar. 21, Sat. Fair, went to Haverhill to Fraternal Rebekah Lodge to see the President and Assembly, staid all night with Ada.

Mar. 22, Sun. Fair, called on Mrs. Bagley and Maud and Bert with Ada.

Mar. 23, Mon. Fair, went to class meeting.

Mar. 24, Tues. Fair, spen the evening with Blanche.

Mar. 25, Wed. Showers, called at Dennis’s.

Mar. 26, Thurs. [$]19 Fair, went up town with Sizzie.

Mar. 27, Fri. Fair, went up town.

Mar. 28, Sat. Showery, went up home with Charles.

Mar. 29, Sun. Rain and snow, came back by train.

Mar. 30, Mon. Rain, went up town.

Mar. 31, Tues. Rain, cleared at night, went up to Stephen’s.

If you are interested in viewing the diary in person in our library or have other questions about the collection, please visit the library or contact a member of the library staff.

*Please note that this diary transcription is a rough-and-ready version, not an authoritative transcript. Researchers wishing to use the diary in the course of their own work should verify the version found here with the manuscript original.

This line-a-day blog series is inspired by and in honor of MHS reference librarian Anna J. Clutterbuck-Cook (1981–2023), whose entertaining and enlightening line-a-day blog series ran from 2015 to 2019. Her generous, humane, and creative approach to both history and librarianship continues to influence the work of the MHS library.