By Susan Martin, Senior Processing Archivist

This is the second installment in a series on the diary of William Logan Rodman at the Massachusetts Historical Society. Click here to read Part I.

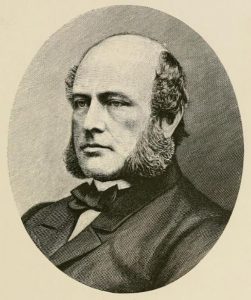

A few weeks ago, I introduced you to William Logan Rodman of New Bedford, Mass., whose diary was recently acquired by the MHS.

When we left him, Rodman was describing the remarkable series of events surrounding Abraham Lincoln’s victory in the 1860 presidential election. Rodman, who supported Lincoln and despised Pres. James Buchanan, initially dismissed all the talk of secession in the newspapers. But then the unthinkable happened. On 20 December 1860, South Carolina became the first state to secede from the Union.

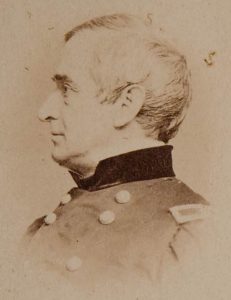

The secession of South Carolina meant that Maj. Robert Anderson, commander of the federal forces at Charleston, suddenly found himself in the middle of enemy territory. Just six days later, under the cover of darkness, Anderson relocated his base of operations from the vulnerable Fort Moultrie on Sullivan’s Island to Fort Sumter in the middle of Charleston Harbor. Although the fort was unfinished, it was solidly built and sat in a more defensible position. South Carolinians were outraged when they awoke the next morning to see the U.S. flag flying over Sumter.

Rodman also reacted to the news with anger, but not at Major Anderson. His target was “the imbecile, traitorous [and] cowardly” Buchanan, who had left Fort Moultrie with few troops and provisions. Rodman wrote, “the people are beginning to swear both deep & loud.”

To say tensions were running high would be a profound understatement. Even solidly Republican Boston wasn’t immune. For example, on 24 January 1861, the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society held its annual meeting at Tremont Temple. The meeting was disrupted by anti-abolitionists, and Boston Mayor Joseph Wightman, who had denied the society its request for adequate police protection, shut the meeting down and locked the doors. In his diary, Rodman scoffed:

What short sighted babydom prevails in Boston. The Mayor fears Ward [sic] Phillips & the Abolitionists will make a riot and so closes the Anti Slavery Convention. Boston gentlemen or rather Boston snobbery must stop the mouths of the radicals and fanatics because forsooth the Traitors of S Carolina wont like it. Bah. The fools make me sick.

In the four months between Lincoln’s election and his inauguration, events escalated at a furious pace. Almost every day brought some new development, faithfully recorded in Rodman’s diary. There was the attack on the ship Star of the West on its way to Fort Sumter with reinforcements and supplies, the resignation of Southern sympathizers from President Buchanan’s cabinet, a rumored plot to assassinate President-elect Lincoln as he passed through Baltimore, and the treachery of David E. Twiggs, commander of the U.S. Army’s Department of Texas, who turned over his entire command to the Confederacy. War was looking more and more inevitable.

Rodman dreaded the possibility of war, but he was also horrified by sentiments such as those expressed by Alexander Hamilton Stephens, vice president of the Confederate States of America, in his “Cornerstone Speech” of 21 March 1861. Rodman called Stephens’ full-throated and unapologetic defense of white supremacy “strange indeed in this enlightened age.”

I would argue that Rodman, in fact, recognized what many of his contemporaries didn’t seem to (or didn’t want to): that no compromise was possible with the perpetrators and defenders of chattel slavery.

Still I am not easy for the Devils of SC may by an attack on Fort Sumter make a new complication. I should like to make some concession to testify my regard for Patriots in the Border States but I dont see how it can be done. Under the garb or style of Compromise we are asked to concede our whole claim and receive nothing in return. It won’t do. Either we are right or we are wrong. If right Lets stick to our position. We are right. So we must stick. Q.E.D.

Like dominoes falling, more Southern states seceded. By the time Lincoln was inaugurated, seven states had left the Union: South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas.