By Susan Martin, Senior Processing Archivist

This is the final installment of a five-part series on the Jarrett family letters at the Massachusetts Historical Society. Click here to read Part I, Part II, Part III, and Part IV.

In this post, I conclude the story of Julia Jarrett and her son Homer, as documented in the Jarrett family letters here at the MHS. Julia had been born into slavery in the 1850s, and in 1909 was living with members of her sprawling family on a farm in Shiloh, Ga. Homer, after years of peripatetic wandering through the Midwest and Northeast, had settled here in Boston, where he would apparently spend the rest of his life. Below is a complete transcription of the fifth and final letter of the collection.

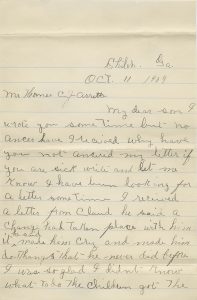

Shiloh. Ga.

Oct. 11 1909

Mr Homer C Jarrett.

My dear son

I wrote you some time but no ancer have I received. Why have you not ancered my letter. If you are sick write and let me know. I have been looking for a letter some time.

I received a letter from Claud. He said a Change had taken place with him. It he said made him cry and made him do things that he never did before. I was so glad I didnt know what to do. The children got the letter out of the box and carried it to the field and I went out thair and they read it to me and I couldent help from shouting and crying and rejoicing.

All at home is well at present. I have been sick for two weeks. I went to see Sister Jane Hawkins. Yesterday Sister Sallie went with me. Sister Jane has been sick but she is better now. Grandpa is well and is try to work as usial.

Homer you must be a good boy and try to prey. I preys mighty for you all and the Lord has give me Claud. He is fix up all right and I trust you is all ready fit meat for the Lord. I trust that I will see you once more in life but if I never see you in life hope to meet you where parten [parting] is no more.

All at home sends love to you. All the children sends their best regards to you. Cora and family is well. Wilson and family is well. The drouth [drought] cut the cotton crops off. We has picked out two bales of cotton but we dont know how many bales we will get. Hasent geathered corn yet.

I remain yours Mother

Julia Jarrett.

This letter was written more than two years after the last. I don’t know whether any correspondence was exchanged in the interim (if so, it may be found in the Homer C. Jarrett letters at the University of Georgia), but Julia’s concern for her son is palpable and touching. She was anxious at not hearing from him and worried not just about his physical, but also his spiritual well-being. Overjoyed at his brother Claud’s new-found commitment to religion, she urged Homer to follow his example and “be a good boy.”

The envelope is addressed to Homer at what looks like #410 A. Col” Ave., which may have been Colonial or Columbus Avenue. He had traveled north at the cusp of the Great Migration, which historians describe as taking place in two waves between 1910 to 1970. Homer would be followed by millions of other African Americans seeking opportunity and escaping Jim Crow. According to National Park Service data, the Black population of Boston, which grew less than that of other Northern cities, still nearly doubled between 1900 and 1930.

Unfortunately I couldn’t find any more information about Julia than I’ve shared in this and previous posts. Homer Clifford Jarrett worked in real estate in Boston and died unmarried in 1959 at the age of 76 or 77. Some of his siblings lived into the 1960s and ‘70s, and amazingly little sister Lizzie lived all the way to 1988. To think that a woman who lived long enough to watch the 1988 Winter Olympics on TV had had a mother born enslaved is to see how few generations removed from slavery we are today.