by Susan Martin, Processing Archivist & EAD Coordinator

This is the second part of a series about the letters to William and Caroline Eustis at the Massachusetts Historical Society. Click here to read Part I.

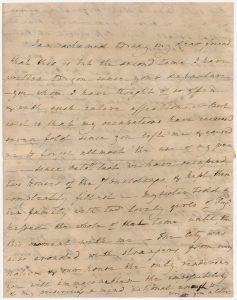

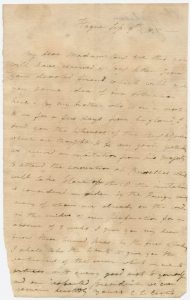

On 17 May 1816, First Lady Dolley Madison wrote to her friend Caroline (Langdon) Eustis. She started by apologizing for not writing earlier, complaining, “my occupations have increased seven fold since you left me, & caused me to forget (allmost) the use of my pen.” This item is one of sixteen that form the letters to William and Caroline Eustis at the MHS.

The letter is apparently Dolley’s answer to one written by her “devoted friend” Caroline, which is also part of the Eustis collection.

Caroline lived at the Hague, where her husband was serving as U.S. ambassador to the Netherlands. He’d been appointed by Dolley’s husband. Caroline boasted about her invitation to the coronation at Brussels of William I, king of the Netherlands, and sent Dolley engravings of William I and Queen Wilhelmine. According to an 1897 article in New England Magazine, Caroline became “a great favorite with the king and queen.”

Dolley’s reply came more than eight months later. In spite of the delay, she assured Caroline of her affection and esteem, as well as that of mutual friends. The names she dropped were a veritable who’s who of Washington wives: Lucy (Payne) Todd, Dolley’s sister and wife of a Supreme Court justice; Anna (Payne) Cutts, another sister and wife of a former U.S. Congressman; Catherine (Murray) Rush, wife of the U.S. Attorney General; and Hannah (Nicholson) Gallatin, wife of the former Secretary of the Treasury and brand-new minister to France. This network of women was key to Dolley’s popularity.

Many books have been written about Dolley Madison and her significant role as First Lady and hostess at the White House, so I won’t attempt to duplicate that work here. A search of our catalog returns 12 published biographies dating from 1886 to 2012, and online sources abound. To me, the most fascinating resource is Paul Jennings’s reminiscences of his years as an enslaved person in the Madison White House, first published in 1865. He called Dolley “a remarkably fine woman. She was beloved by every body in Washington, white and colored.” (It should be noted that the memoir is a transcription of Jennings’s recollections written “in almost his own language” by John B. Russell.)

1816 was a remarkable year in the history of the nation’s capital. Just two years before, in the midst of the War of 1812, British troops had marched into the city and set fire to many of its buildings, including the White House and the Capitol. With the White House gutted, the Madisons moved to the “Seven Buildings,” a row of townhouses a few blocks away on Pennsylvania Avenue. When she wrote this letter to Caroline, the Madisons and some extended family members filled two of the seven residences. Dolley’s 24-year-old son John Payne Todd, her “darling Payne,” was also with her at this time. (Payne was her son from her first marriage and her only surviving child. Her first husband and another son had both died of yellow fever on the same day in 1793.)

But now the war was over, and, as Dolley explained, the bustling city was “in a state of great improvement” and “crowded with strangers from every Nation.” However, overwhelmed with familial and social responsibilities, she was already looking forward to the end of her husband’s presidential term and the family’s return to their home at Montpelier, Virginia.

One of the things I like about doing these deep dives into a single manuscript is that it gives me the opportunity to learn more about a specific historical moment and the individuals involved. There’s almost always something interesting or surprising to uncover. Writing about this particular collection also allows me to highlight the work of our digital team, which has fully digitized all sixteen letters. We hope you’ll explore more of the letters to William and Caroline Eustis and the stories behind them.