by Susan Martin, Processing Archivist & EAD Coordinator

This is the seventh and final post in a series. Read Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, Part V, and Part VI.

For the last few months, I’ve been telling you about the letters of Dwight Emerson Armstrong of Wendell, Mass., who served with the 10th Massachusetts Infantry in the Civil War. Today we conclude his story.

Things were quiet for the 10th after the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862, which was just fine by Dwight. He did take part in Ambrose Burnside’s Mud March of January 1863, in which troops, artillery, and pontoon trains were trapped in a days-long downpour and got so bogged down in the mud that they had to give up and turn back. But after that disastrous march, the regiment settled in for the rest of the winter at the Union camp near Falmouth, Va. on the north bank of the Rappahannock River. Dwight called the lull “very agreeable to a man whose constitution will bear as much rest, as mine will.”

In early February, ten-day furloughs were granted on a very limited basis, but Dwight didn’t bother to request one because the time would be too short and, as he wrote his sister Mary (Armstrong) Needham, “if I should get there I should’nt want to come back. […] Do you know that it has been almost 2 years since I saw you.”

Of course, by mid-February, Dwight was complaining of boredom. The soldiers entertained themselves as best they could. On 7 March, Dwight and others attended a local “negro meeting,” which he described in detail in a letter to Mary the following day. He found the experience novel and amusing, writing, “I guess I laughed as much as ever I did in the same length of time.”

Apparently, Mary took exception to his mocking tone. (Our collection unfortunately doesn’t include her letters). Dwight replied to her more seriously a month later.

As for what you say about your not laughing, if you had been at the negro meeting I dont believe it. No doubt it was wrong to do it; but I’ll bet, you would have laughed, down in your stomach, all the while. […] No doubt they are sincere in their worship. It is strange, after being kept under, and abused, as they have been for generations back, that they are half as intelligent as they are. They seem to understand what is going on pretty well, and are loyal, and earnestly wish, and pray, for the success of our arms. […] They evidently are impressed with the belief that the good time is coming; when they will all be free and I dont see how any sane person can doubt it. How soon it will be, we dont know but I for one think […] we are only in the beginning of the war.

Dwight admitted that he’d underestimated the resilience, resourcefulness, and determination of the South, although he still believed the North would win the war, if for no other reason than that its army was larger. As he put it, “we have a good chance to break them and have a few left to start again with.”

On 8 April 1863, the Union troops were reviewed at Falmouth by President Abraham Lincoln himself, accompanied by General Joseph Hooker. Dwight had been harshly critical of Lincoln in previous letters, had even referred to him as “mad,” but now found his heart going out to him.

The President looks as if he was almost worn out. Poor man! I pity him, and wonder he is alive, surrounded as he is by such a pack of traitors, and numb skulls, and he the only honest man in the lot. I have scolded, a good deal about him, since he removed McClellan, and wished him in the bottom of the ocean, but was ready to forgive him, when I saw how pale and sorrowful he looked.

The last letter in the collection was written on 27 April. In it, Dwight primarily discussed mundane matters, but he also had this to say about the Confederate army: “If we could only drive them, off from the hills, on the other side of the river, so as to meet on equal terms I should have no fears of the result and have’nt as it is, much.”

Dwight was killed six days later on 3 May 1863 in the Battle of Salem Heights (or Salem Church), Va. He was 23 years old.

Coincidentally, the MHS holds a diary written by another member of Dwight’s company, Private George Arms Whitmore. Here’s an excerpt from George’s diary entry for that day:

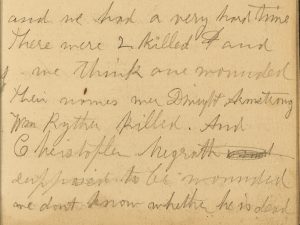

In the afternoon we drove the rebels about 3 miles when they made a stand and we had a very hard time. There were 2 killed and we think one wounded. Their names were Dwight Armstrong Wm Ryther killed. And Christopher Megrath supposed to be wounded.

William Eaton Ryther was a 20-year-old from Greenfield, Mass. According to a history of the town, he and Dwight were buried on the field together. Dwight’s body was apparently later removed to Locust Hill Cemetery in Montague, Mass., where he’s buried with his parents.

Joseph K. Newell’s history of the 10th Regiment tells us that Christopher Megrath survived the battle and the war, but died in 1869 as a result of the wound he received that day.

Dwight’s sister Mary, to whom he wrote so faithfully, died in Springfield, Mass. in 1887.

Thank you so much for share your thoughts

For Know more visit : – https://kiranivfgenetic.com