Susan Martin, Processing Archivist & EAD Coordinator

This is the fifth post in a series. Read Part I, Part II, Part III, and Part IV.

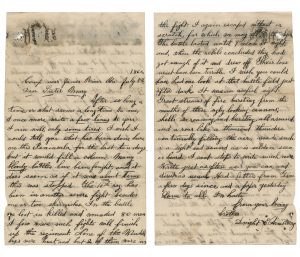

I am well, only some tired. I wish I could tell you what has been done here on this Peninsula for the last ten days but it would fill a volume. Many bloody battles have been fought, and it does seem as if it was about time this was stopped. […] I wish you could have had one look at that battle field just after dark. It was an awful sight. Great streams of fire bursting from the mouths of these ugly looking cannons; shells screaming, and bursting, all around, and a roar like a thousand thunders, continually filling the air, made such a sight and sound as is seldom seen or heard.

These words were written by Dwight Emerson Armstrong of the 10th Massachusetts Infantry in a letter to his sister Mary (Armstrong) Needham dated 5 July 1862. Since his last letter, Dwight had fought in several battles and skirmishes near Richmond, Va., one after the other in quick succession, culminating in the Battle of Malvern Hill. This series of engagements became known as the Seven Days Battles. Union troops were now “taking breath” in the relative safety of camp at Harrison’s Landing on the James River.

The MHS collection of Dwight’s letters unfortunately doesn’t include Mary’s replies, but we know she had some questions, which he answered when he wrote next two weeks later. What had the Union gained in those brutal seven days? Dwight replied, “I dont think we have made out much of anything.” Would they attempt to take Richmond again? Not likely, until reinforcements arrived. What were the prospects for peace? Dwight was understandably cynical.

When there is a union between the Powers of Light and Darkness you may look for Union between the North and South and not till then. […] A few weeks more of such fighting as the last week was, will pretty much use up the present generation.

At just 22 years old, Dwight was now an experienced soldier and had learned a lot. For example, he admitted that he’d underestimated the enemy.

The rebels are no cowards, and mean to fight to the last. They are perfectly desperate in battle, and care very little for bullets. Their Generals seem to care no more, for the lives of their men, than they would for the lives of so many flies. […] They would march their men in 5 or 6 great long lines, one behind the other, straight up to our batteries, that at every moment mowed them down by hundreds, I never saw such slaughter.

The 10th Regiment was stationed at Harrison’s Landing from 2 July to 16 August 1862, when it pulled up stakes and headed north. During the summer and fall of that year, Dwight wrote less frequently, only about once a month, due to the regiment’s many relocations and engagements. He was near enough to hear the fighting at Antietam, Md., on 17 September, but by the time the 10th was ordered to the field, that bloody battle was essentially over. Dwight saw only the aftermath, but the scene made a distinct impression.

I went around on the battle field, after the fighting was over, and the sights beat all that I ever saw. Men lay piled up in winrows and dead horses broken cannons, and everything else; covered the ground. […] I suppose this war is to go on until, all the men each side can raise are killed off, and then they will be satisfied.

A new concern cropped up in Dwight’s letters at this time—his brothers. He was disheartened by the news that his older brother, Timothy Martin Armstrong, had enlisted. Another brother, Joel Mason Armstrong—Mason, as he was called—also enlisted on 5 September 1862, according to that invaluable reference Massachusetts Soldiers, Sailors, and Marines in the Civil War. Mason was a carpenter in Sunderland, Mass., and would serve in the 52nd Massachusetts Infantry until he was mustered out the following summer. You can read a little more about Mason in A Record of Sunderland in the Civil War (p. 14).

However, Timothy never enlisted, as far as I can tell. This is confirmed in a letter from Dwight to Mary on 25 November 1862. Dwight regretted that Mason had gone to war, but was relieved Tim was staying out of it.

I think one out of the three, ought to know enough to stay at home and not come off here to quarrel about politics; that is all the fuss is about any way. It is just like two parties going to town-meeting, and getting into a knock-down fight, about their opinions. Perhaps it was not so when the war first commenced, but it is now.

Both Tim and Mason would live into their seventies, dying in the early years of the 20th century.

It was two days before Thanksgiving 1862, and Dwight found himself even farther from home than the previous year. He realized his earlier optimism was misguided and the war would likely drag on for some time.

I hope you’ll join me for the next installment of Dwight’s story here at the Beehive.