By Susan Martin, Processing Archivist & EAD Coordinator

This is the third post in a series. Read Part I and Part II.

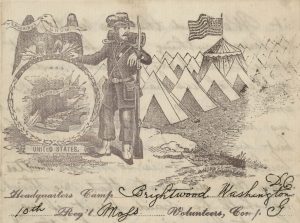

When we left Private Dwight Emerson Armstrong in the fall of 1861, he and his regiment, the 10th Massachusetts Infantry, were stationed at Camp Brightwood (later Fort Stevens) in Washington, D.C. Dwight had seen no action yet, but was anxious to join the fight. Rumors abounded, both in camp and up North: the war would be over in a month or last another year; D.C. was in danger of imminent attack or perfectly safe; the regiment would be sent into battle at any moment or assigned to guard the nation’s capital; the troops were winning great victories or merely stumbling through inconsequential skirmishes.

Camp Brightwood was comfortable, and the soldiers had grown accustomed to the sound of nearby gunfire and cannon blasts, but the uncertainty irritated Dwight. His letters to his sister Mary (Armstrong) Needham in October 1861 were his bitterest yet, full of angry underlining for emphasis.

They have got old Armstrong this time but if Uncle Sam ever gets into another row with his rebellious children I know of one who wont help him chastise them, even if the old gent got whipped himself individually. Here they are keeping this great army here in idleness waiting for what; if anybody knows I wish they would tell. I believe that the officers are afraid to attack the rebels; it look[s] like it certainly and if they are not, why dont they do it.

In fact, the delay was making him cynical about the whole idea of reunification, and he told Mary that the Union should just fight or go home: “Now if the South cant be beaten why not give up at once and let the whole government go to eternal smash and have it done with.”

He’d started writing more broadly about the war and politics, criticizing the U.S. army for, among other things, their “foolish” attempt to starve the South “into submission.” There was also the undeniable fact that the Confederacy had chalked up a number of victories on land and sea, which called into question the reassurances of Northern generals. Dwight even began to doubt that God was on the side of the Union!

On 5 December 1861, Dwight reached the ripe old age of 22. Five days later, he wrote to Mary in a more introspective vein.

Many things have happened in the 22 years I have seen that we little thought of and how many, many things will happen during the next 22 years that we little think of now. It is true as you say we are all weaving the web of life and nations as well as individuals must play the part designed for them in the beginning and though we poor wretches often think that the machinery don’t work right yet doubtless in the end we shall all see that the jolts and wreckings were a part of the great plan and without which the web could not have been perfect.

Up to this time, he’d mentioned slavery only once or twice, but on 12 January 1862, he discussed the subject at length. He started by describing the “contrabands” at Camp Brightwood, enslaved people who’d escaped to Union lines.

We have got quite a lot of “contrabands” in our camp and they are very useful. Money would not hire one of them to set his foot out side of the camp for fear his master would get him. The slave as a class are much more intelligent than the white folks; after all that has been said about their not being able to get their own living and the like. P.M. General Blair has got some of the nicest slaves I ever saw. I wish I was half as smart as some of them.

(Montgomery Blair was Abraham Lincoln’s postmaster general from 1861 to 1864. Blair lived nearby and, according to Alfred S. Roe’s history of the 10th Regiment, had visited the camp the previous October.)

Dwight went on to compare the enslaved people and free black people he’d seen in D.C. The freemen were “as much poorer than the poorest people at the North as you can think” and usually had to beg for subsistence. Most slaves, he said, were not only more intelligent, but better fed and clothed, so they felt superior to and mocked “their free brethren” when they met in the street. Knowing this, “the free shun[ned] the slaves as they would a pestilence.”

The collection unfortunately doesn’t include Mary’s reply, but we can fill in the blanks from Dwight’s next letter. On 21 January, he clarified:

You want to know why the slaves want to be free if they were much better off then [sic] their colored brethren. It is true that all the slaves I have seen are much better off in every respect than the free negroes. But there is no such thing as a man’s being contented in slavery so long as there is a single spark of humanity in him. Most of the slaves I have seen, seem to be pretty well contented, but after all they aren’t, and never can be, so long as they have a master.

The 10th Massachusetts Infantry left Camp Brightwood on 10 March 1862 after a seven-month stay. For more “jolts and wreckings,” come back for Part IV of Dwight’s story here at the Beehive.