By Susan Martin, Processing Archivist & EAD Coordinator

This is the fourth post in a series. Read Part I, Part II, and Part III.

Today we return to the Civil War letters of Dwight Emerson Armstrong of the 10th Massachusetts Infantry. In March 1862, Dwight’s regiment left Camp Brightwood in Washington, D.C. and traveled south into Virginia as part of the Union advance on Yorktown. On 15 April, he wrote to his older sister Mary (Armstrong) Needham from his position near Warwick County Courthouse. The siege of Yorktown was underway.

As for the “miserable war” so far, Dwight had this to say:

I have not done much but lug a gun around. I dont want to come home until the war is over, now I have got here; but I sometimes almost think, that the Union costs rather more than it is worth. It sounds very well, for these great men, who live in good warm houses; and on the fat of the land; to preach of the value of this glorious Union but let these same men come down here and stand as picket guard some night in a pelting storm; and if they dont get some of their patriotism washed out before morning, I’ll lose my guess. Still I would not have you think that I am discouraged […] and as long as I can have the privilege of grumbling, [I] shall get along nicely.

Much of his time was occupied with repairing roads. The army’s wagons and artillery tore up the roads, rain filled the enormous holes left behind, and soldiers like Dwight were assigned to shovel mud into the holes to keep the roads passable. He understood the necessity of the work, but complained, “I dont think much of coming down here to mend their highways for them but I suppose I cant help it.”

Though he was bitter about the “great men” in their “good warm houses” and resented the drudgery of his work, he defended George McClellan against criticism that the general acted too slowly and cautiously. He called McClellan “a different sort of a man [who] cares something for a man’s life.” In fact, after a year of service, Dwight didn’t think he’d ever see much fighting.

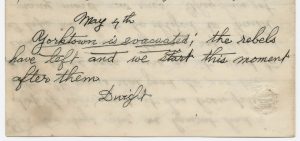

On 4 May 1862, Confederate troops evacuated Yorktown, and the Union army, including the 10th Regiment, pursued them west across Virginia. The two sides faced off in the Battle of Williamsburg the following day, but by the time Dwight reached the front lines, the fighting was already over. He was both frustrated and relieved: “I have had no chance to fire again at the rebels yet, and there is no prospect of my ever having a chance to, and I am sure I dont want to, after what I have seen.”

He didn’t elaborate, but he may have been referring to the bloody aftermath of the battle, as described by Joseph K. Newell in his 1875 history of the regiment. Newell writes about the Southern soldiers unable to retreat: “Men wounded in every shape; some dead, and some dying; many shockingly mangled, to whom death would have been a blessing.” (p. 90)

Union forces continued their march west, closing in on Richmond. Dwight didn’t even know if the Confederate army was still in the city, but he hoped they would just get it over with, make their stand “until they get enough of it, and are willing to give up. I am tired of chasing them.” His regiment was positioned about eight miles from Richmond, at Fair Oaks.

It was here that Dwight would see his worst fighting yet. The Battle of Fair Oaks (or Seven Pines) broke out on 31 May 1862. The attack was unexpected, according to Newell, “like a clap of thunder from a clear sky.” (pp. 98-9) The Union army was driven back and suffered heavy losses.

Dwight wrote a short note to his sister after the battle to let her know he was alive and unharmed, but didn’t go into much detail until 14 June.

You want to know how I felt while in battle. Well, I suppose I felt pretty much as you would to stand out and have shot, and shell, and all sorts of missiles thrown at you. I have often read that when a man goes into battle, he loses all fear, and only thinks how he can kill the enemy the fastest. I can imagine how a man, if he was nervous enough, could get worked up to such a pitch of excitement that he would lose all fear for himself; and dont doubt it is so in some cases; but so far as my experience goes it is quite the contrary. For my part, I am not at all ashamed to own that I was some afraid at first, though the thought of turning around and running away never crossed my mind. It is perfectly astonishing what an immense amount of lead it does take to kill a man. If a single thousandth part of the missiles thrown the other day had taken effect every man on the field would have been killed the first hour. Bullets sometimes come pretty close to a man without hurting him any but if a cannonball or a shell hits a body of men it makes bad work. […] The bullets tore up the ground under our feet, and whistled terribly close to our ears, and fell all around us like hailstones; and it seems miraculous that no more were hurt.

The captain of his company, Edwin E. Day of Greenfield, Mass., was killed at Fair Oaks. Dwight witnessed his death. Under heavy fire, Day’s men were forced to leave his body behind, but when the fighting was over, they buried him “as decently as possible.” After the war, his body was retrieved from Virginia and interred at Greenfield.

Dwight finished his letter by reassuring his sister, as he had many times, to “keep up good courage and dont worry about me.”

I hope you’ll join me for the next installment of Dwight’s story here at the Beehive.