By Susan Martin, Processing Archivist & EAD Coordinator

This is the second post in a series. Part I can be found here.

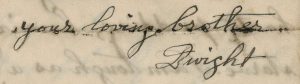

On 16 July 1861, after a month at the Hampden Park training camp in Springfield, Mass., the men of the 10th Massachusetts Infantry began their journey South. Among them was Private Dwight Emerson Armstrong, whose letters to his sister Mary were recently acquired by the MHS.

The regiment passed through Medford, Mass., where they camped on the banks of the Mystic River at what Dwight called Camp McClellan. (Regimental histories by Joseph K. Newell and Alfred S. Roe use the name Camp Adams; the land had once belonged to John Quincy Adams.) This location was practically idyllic compared to Hampden Park, but the respite was short-lived. Just five days later, the first major battle of the Civil War broke out.

The First Battle of Bull Run, known to the Confederates as the First Battle of Manassas, was fought near Manassas, Va. on 21 July 1861. Dwight heard via telegraph that “the rebels were beaten and 1500 stand of arms taken and a 1000 prisioners.” But these initial reports were wrong—the battle was a terrible loss for the Union Army, and the 10th Regiment was ordered to move to Virginia sooner than anticipated. Dwight gamely told his sister Mary, “I hope we shall not have to stay a great while and I don’t beleive it is going to be a long war.” On 23 July, he wrote his last letter before leaving Massachusetts, closing with “about 900 pounds” of love to his nieces Annie and Jennie.

By 28 July, Dwight and his regiment had reached the Washington, D.C. Navy Yard. He described to Mary the steamer journey up the Potomac River, between the Confederate state of Virginia and the border state of Maryland. He saw a few masked rebel batteries, Mount Vernon (“a most beautiful place”), and “two or three old dillapidated looking negroes,” but no enemy soldiers so far.

In fact, Dwight was preoccupied with and angry about the army’s provisions, which consisted entirely of hard bread and rotten ham…for the enlisted men. He blamed Quartermaster John W. Howland and the commander of the regiment, Colonel Henry S. Briggs. It wouldn’t be the last time he wrote in such defiant tones.

I know it is a serious offence to say anything about our officers but I don’t care when I get mad and I will say that we have got a Quarter-master that don’t know enough to go in when it rains and a Col. that so long as he can keep his own contemptible old stomach full of beef steak don’t care what his men have to eat.

The next letter in the collection is dated 12 September, more than six weeks later. By this time, the 10th Regiment had settled at Camp Brightwood (a.k.a. Fort Massachusetts, a.k.a. Fort Stevens) in northwest Washington, D.C., which would be its home for seven months. Brightwood was one of dozens of encampments constructed during the war to improve the capital’s defenses. In one interesting passage, Dwight described building fortifications, which necessitated the destruction of a local church.

We have been at work for sometime past building batterries; and have not got through yet by considerable. It is a great deal of work to build them but there are a great many to do it. […] The first one we built has got a good brick meetinghouse inside of it. It stood on a hill right where they wanted the battery so the meetinghouse has got to be pulled down. […] It seems a pity to take it down for the heathen want it or at least need it as bad as they do any where but in war time they dont stop for meetinghouses nor anything else.

This church, the Emory United Episcopal Church, whose bricks were literally pulled down and used to build the fort, was later rebuilt and operates today as the Emory Fellowship. Fort Stevens is a national park, and some of its earthworks still exist.

Dwight was optimistic about the outcome of the war, felt safe at Camp Brightwood, and was adjusting fairly well to military service, despite the nits and cockroaches that were, in his words, “just like the Southerners never satisfied with what they have got but always want more territory.” The food had even improved since the “Quartermaster was very Providentially taken sick.”

He’d seen no combat yet, but every once in a while an alarm was raised, and the troops were “tumbled out of [their] tents” and held in readiness to march at a moment’s notice. None of these alarms had come to anything, and Dwight found the whole thing kind of amusing.

It is curious how anyone can get used to almost anything so as to not mind anything about it. […] They were having a battle only a few miles off and we could hear the cannons thundering away almost as plainly as if we had been there but we had got so used to disturbances of this sort that no one minded anything about it and all laid down with their guns beside them and went to sleep as quietly as though they were a thousand miles from any danger.

Please join me for the next installment of Dwight’s story!

Dwight Emerson Armstrong was my great-grandfather’s brother. I have several letters from my great-grandfather and one from Dwight written in Sept 1861 while stationed in the DC area. I have the letter from my great-grandfather where he acknowledges hearing of the death of his brother. I’ve made scans of these letters and will email them to you if you like.

I have one letter from Dwight to his brother and the envelope it was mailed in. I also have several letters from his brother to their sister. I’ve had them for years now and I’m worried that they might deteriorate too much in my possession. I’m not looking to sell them, I want to donate them to someone who will appreciate them and keep them safe.

This is my second comment, please respond.