by Daniel Hinchen, Reference Librarian

On this date in 1845, Macon Bolling Allen became the first African American admitted to the bar in Massachusetts. In the May 9, 1845 issue of William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator, made note of Allen’s new standing in the Massachusetts legal world:

Macon B. Allen, Esq. lately of the Portland Bar, is, we observe, engaged in the practice of the law in this city. Mr. Allen is now a member of the bar of Suffolk, admitted here on examination. . .

But, as this little blurb intimates, while Allen was the first African American to be admitted to the bar in Massachusetts, it was not the first place Allen was admitted to the bar.

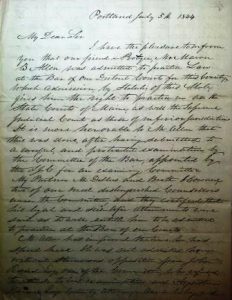

(Massachusetts Historical Society)

Nearly a year earlier in July of 1844 Allen was admitted to the bar in the state of Maine. Prior to his examination in Maine, Allen studied law in the offices of two white abolitionist lawyers, Samuel E. Sewall and Samuel Fessenden. On July 5, Fessenden wrote to his law partner proclaiming the news of Allen’s successful examination. His success, though, was not without opposition, and Fessenden recognizes that Portland may not be the best place for Allen to ply his new trade. The letter in-full reads:

Portland July 5th 1844

My Dear Sir

I have the pleasure to inform you that our friend & protege, Mr. Macon B Allen was admitted to practice Law at the Bar of our Distric Court for this County, which admission, by Statute of this state, gives him the right to practice in all the state courts of Maine, as well the Supreme Judicial Court as those of inferior Jurisdictions. It is more honorable to Mr. Allen that this was done, after having submitted to a careful, and protracted examination by the Committee of the Bar, appointed by the SJC for an examining committee. My Partner Mr. Deblois and Brother Howard, two of our most distinguished counsellors were the Committee, and they certified that his legal and scientific attainments were such as to well entitle him to be admitted to practice at the Bar of our Courts

Mr Allen has improved the time he has spent here. He was not admitted however without strenuous opposition from John Rand Esq, one of the Committee, who refused to attend to his examination, and Augustine Haines Esq County Attorney, One a Whig, and the other a Democrat. Of course I warmly advocated his admission. Judge Goodenow who held the Court, though not an antislavery man, acted nobly, and said he could not, sitting on that Bench of Justice, have respect to the colour of the skin.

It was contended that to admit Mr. Allen woudl disgrace the Bar, no doubt because he was a coloured man, though that was not in terms avowed. His qualifications were not denied. I think Mr. Allen had the sympathy of a large protion of the people in the court, and some & I think quite a number of the jurors wept while I addressed the Court which I did much at large, on the rights of the coloured man, and the wickedness of that prejudice which was crushing him. I think the event will do great good. Rand & Haines are active politicians, & only agree in an inveterate hostility to the antislavery cause.

I regret that Mr Allen has to struggle with poverty, as I have been compelled to advance him the $20 duty or tax which our statute imposes, an admission to practice at the Bar, and some small sums beside to enable him to live. I hope he will be aided to repay me as I shall also be compelled to stand [security]for his bond while here. This regret I should not feel were I not myself a poor man –

I hope however the cause of truth will be advanced, by the victory which we have obtained. Deblois & Howard did their duty though I could perceive, they dd not wish him to be admitted. But they had too much honor and too high a sense of justice to refuse a certificate, fairly claimed by merit.

The cause of emancipation is [onward] in Maine. I have recently been in some of our Eastern Counties, and fully believe the genius of liberty is arousing from her slumbers. I made several antislavery addresses on my route. I feel to thank GOD & take courage.

I incline to think Portland is not exactly the place for our friend. Our coloured people here are few and poor; and Portland, altogether, is an inveterate proslavery place.

with regards

your friend and obt servant

Samuel E. Sewall Esq Samuel Fessenden.

Despite – or maybe because of – his position as a trailblazer, Allen found difficulty obtaining clients. According to American National Biography, late in 1845 Allen complained in a letter to John Jay Jr. of New York, that New Englanders preferred famous or well-established lawyers. But, things got better quickly for him. In 1847, Allen was appointed a justice of the peace by the governor of Massachusetts, a Whig, which made him the first African-American appointed a judicial official in the United States.

Following the Civil War, Allen and several other African-American lawyers and activists migrated South. In 1868, he joined Robert Brown Elliot and William J Whipper in Charleston, South Carolina, in establishing the first known African-American law firm in the country, though they represented clients of both races.

Though he never attained high political office, in 1873 Allen was elected a judge of the Inferior Court by the South Carolina legislature, and in 1876 was elected to probate court and served through 1878. Following that stint he returned to his legal practice in Charleston.

Macon Bolling Allen died in 15 October 1894, leaving behind an unnamed widow and a son, Arthur W. Macon.

Sources

Fessenden, Samuel to Samuel E. Sewall, 5 July 1844, Robie-Sewall family papers, Massachusetts Historical Society.

Smith, Johnie D., “Allen, Macon Bolling (1816-15 Oct. 1894).” In American National Biography, edited by John A Garraty and Mark C Carnes. Oxford University Press, 1999.